| Registry Working Group | |||

| Links: | Registry Twiki | Registry Mail Archive | IVOA Members |

|

|

||||||||||||

| International Virtual Observatory Alliance | |||||||||||||

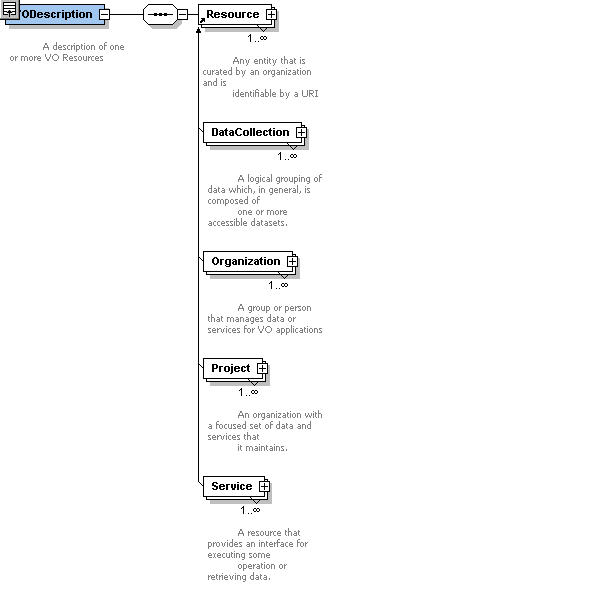

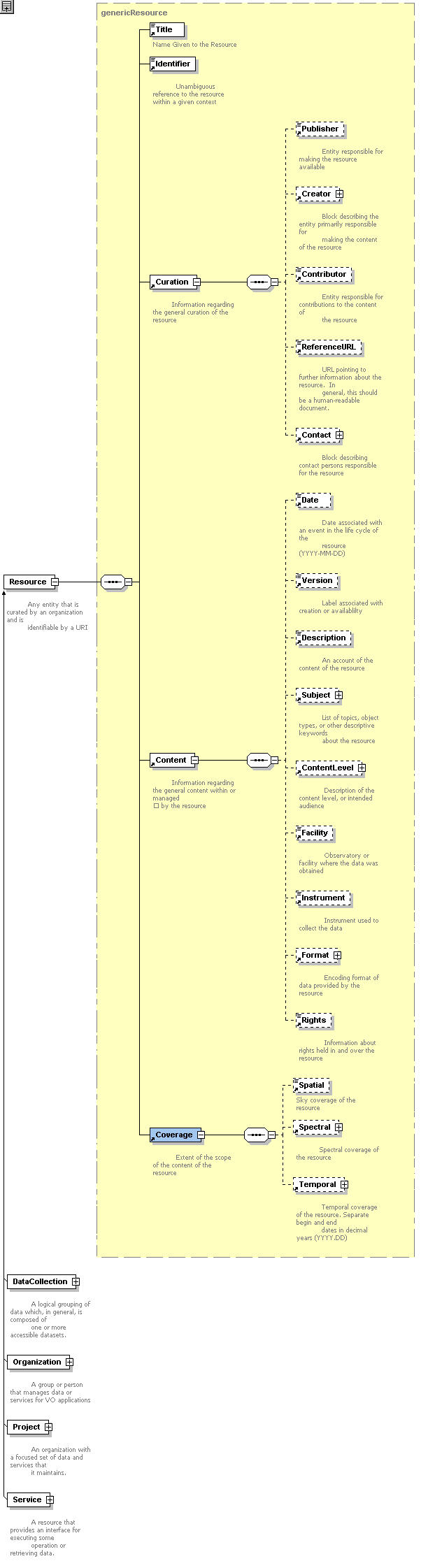

Resource element.

Figure 2 illustrates the structure of this

metadata; the yellow box (representing a genericResource

type) encloses the common Resource metadata. In includes three main

catagories: Curation, Content, and

Coverage.

Figure 1: The different types of Resources |

Figure 2: Generic Resource and Service Metadata

|

The second principle recognizes that different types of resources

require addition metadata to describe that is not common to the other

types. This schema provides a way to "hook" on this extra metadata

using a combination of XML type extension and XML substitution groups

(see section 2.2 below). In a real sense, the

Organization, Project, DataCollection,

and Service elements inherit

from the generic Resource. Resources that don't match one of these

"sub-elements" could be described by the generic

Resource element, or additional sub-elements

could be defined to accommodate. The arrows in Figures

1 and 2

indicate that a sub-element can be substituted in anywhere that a

Resource is expected. The

VODescription element is provided to

allow a listing of Resources of different types.

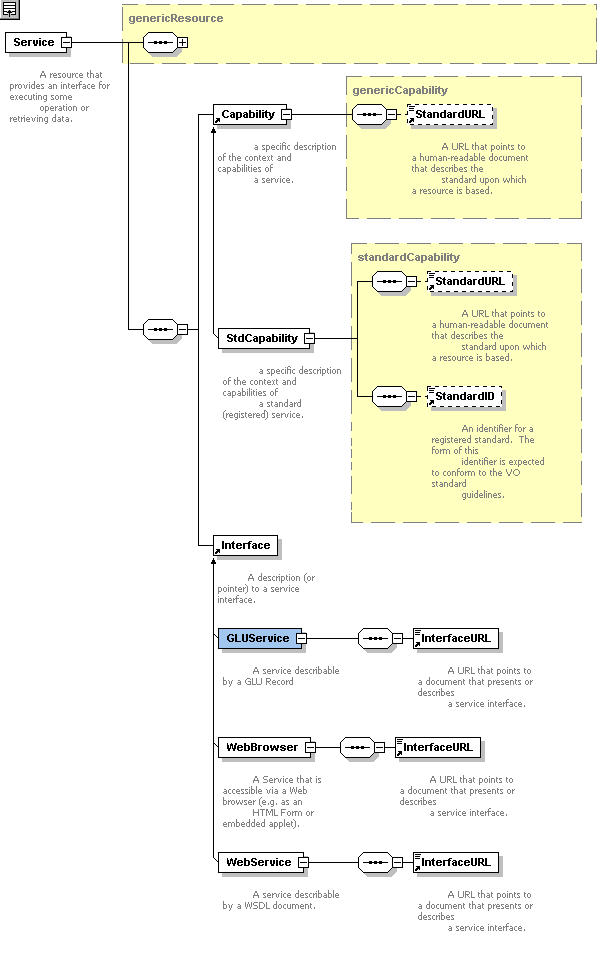

The Service element extends

Resource to add two additional child

elements: Capability and

Interface (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Generic Service Metadata.

The Interface element is an extension

point for describing different types of interfaces, such as Web

browser-driven forms (WebBrowser) and

Web Services (WebService). The

WebService simply provides a place,

InterfaceURL to point to a WSDL

document.

The Capability element is place to place

all metadata that does not fit well into the interface description.

The StdCapability sub-element is meant

for describing standard services such a Simple Image Access or Cone

Search. This is described below.

1.2 Support for Simple Image Access Protocol

The metadata specific to Simple Image Access has been separated into

another schema, VOStdService. The

SIA's interface is described with a

ParamHTTPGet element (a sub-element of

Interface); this holds the supported

input parameters, the BaseURL, and the

MIME type of the output (see Figure 4).

The SIA specification defines a special set of metadata which are

interpreted here as part of its "Capability". In this schema, the

StdCapability is extended to produce the

SimpleImageAccess to hold that metadata,

as shown in Figure 5. The

VOTableColumns element is meant to list

the VOTable Field tags that describe the

VOTable output columns. In both figures below, the "vot"

namespace prefix indicates elements borrowed from the VOTable schema.

Figure 4. SIA Interface represented as a ParamHTTPGet element.

|

Figure 5. Simple Image Access and related metadata.

|

I note that the separation between VOService and VOStdService is not

as clean as it should be. (The separation was mainly guided by

experimentation and debugging needs.) The

ParamHTTPGet should be moved to

VOResource as one of general service interface types. Furthermore,

VOStdService should be specialized (at least in name) to just SIA.

Other standard services should have their specific metadata in their

own separate XML Schema documents.

1.3 Sample XML Document

The example, adil.xml, uses a

VODescription to list four resources

associated with the NCSA Astronomy

Digital Image Library: a Project, a

DataCollection, and two

Service records. The first service is

just the browser-based search page for the Library, and the second is

the SIA interface. Note that the author did not feel the need to fill

out values every possible metadata tag in the schema. In particular

within the SIA's service description, the supported input query

parameters and the output columns were not included; this information

can be added latter by an automated service verifier.

2. General Approach

The various goals I've tried to keep in mind fall into four catagoies;

that is, the XML Schema should:

2.1. Clarity and Reuse

I attempt to achieve the first goal with a schema model that is a

close reflection of we think about and use metadata. If the match is

good, it should be easy to automatically transform the XML Schema

(using XSLT) into a human-readable metadata dictionary that uses a

minimum of XML jargon to describe itself. To achieve this, the schema

model needs to capture components that define a metadatum:

In my mind, when it comes to handling metadata, the meaning is as

important as the type--but they are not the same thing. A type

defines the form the value comes in; it's a container with no

meaning. For example, calling something an integer or a string

doesn't tell you what the value represents, and an integer can be used

to hold values that represent very different things. A value of a

certain type becomes a metadatum when meaning is attached to it,

represented by its name.

In object-oriented languages, the distinction between type and meaning is fuzzy. A Vector class is a generic container that carries no particular meaning; its methods are usually about accessing its components. A Screen class, on the other hand, has meaning, and therefore, it might include other methods that control how it works meaningfully with other classes, like Window and Scrollbar. Fortunately, XML Schema makes a distinction between elements and types which we can take advantage of.

Thus, the metadatum components are captured in the following way:

This provides a natural way of interpreting an XML instance document,

independent of a schema: the element name represent the meaning of the

values it contains.

Also as a way of aiding clarity, a metadatum should have a general

meaning that is independent of how it is used. It's role may be

somewhat different when it is used as a component of different, more

complex metadata. Nevertheless, its general meaning does not change,

and its type does not change. To enforce this,

(The correllary to this is that complex elements will define their

content using the ref= mechanism.) Not only does this

encourage the reuse of elements to describe different things, it

enforces consistant use of the element. A "Frequency" element can be

used to describe a bandwidth or an observation. In both cases, the

meaning of Frequency and form that it takes should be the same.

The only few elements that are defined locally (i.e. within a

complexType without using a ref attribute),

are ones that have no particular meaning to them but just provide

structure. For example, an item element is defined to

delimit elements in a string array. Capitalization is used to

emphasize the difference:

2.2. Extensibility

The Resource metadata is a good example of why extensibility of the

metadata model is important. New standard services will have a unique

metadta associated with them, and so we need a way to integrate them

as we go.

An important XML Schema feature

VOResource uses to enable extension is

the substitutionGroup attribute in the

definition of elements. This defines an element that can be used in

place of another; when comined with the XML's version of

inheritance--namely, extension and restriction--they provide

a form of polymorphism. In the VOResource example, a

Service element can be used anywhere a

Resource element is expected. The

difference is that the Service element

will contain service-specific metadata not applicable to a generic

Resource.

Proper declaration and use of namespaces is important when extending

or reusing metadata. For example,

VOStdResource draws upon the

definitions in both VOResource and

VOTable. In order to allow other

schemas to extend or reuse elements in a schema, I found it is

important to always define a

targetNamespace. Although the current official

VOTable follows the pattern sugested in the

previous section (e.g. globally defined

elements), it does not define a namespace, preventing me from mixing

VOTable elements with elements from VOStdResource. To get around

this, I created a new version of VOTable.xsd, slightly modified to

define the target namespace.

2.3 Integration with Tools

There are a number tools that make it easy to build XML-based

applications. Most notable are those that automate the building of

Web Services; these include for example, Java's APIs for XML Binding

and Messaging (JAXB and JAXM), Apache's Axis, and Microsoft's XSD.

The power of these tools is in their ability to automatically generate

software classes directly from the XML Schema document. Tools that

help integrate XML with relational databases are also expected to be

important. A schema authoring style that allows for the use of these

tools ultimately reduces the software VO developers will need to

write.

Experimentation with such tools is on-going. Developers at STSci/JHU

(Wil O'Mullane and Gretchen Greene) have used Microsoft's XSD to

create C# classes. It appears that substitution groups are not well

supported by current tools; however, it is expected that they will

before long.

2.4. Conclusion

This exercise has revealed several straigh-forward patterns for

defining and extending metadata using XML Schema, most of which have

not been described here. These will enumerated in detail in a

subsequent document.